How does a cardioversion work?

An electrical cardioversion delivers a controlled electric shock to the heart to reset atrial fibrillation (AF) back to a normal sinus rhythm. In previous posts, I described cardioversion as an effective rhythm-control treatment for many people due to its quick effect and high safety profile.

But how exactly does it restore a normal rhythm? Understanding the science behind cardioversion can help us appreciate why AF occurs, and why some people experience AF relapses after rhythm-control treatments like ablation, while others don't.

What is an electrical cardioversion?

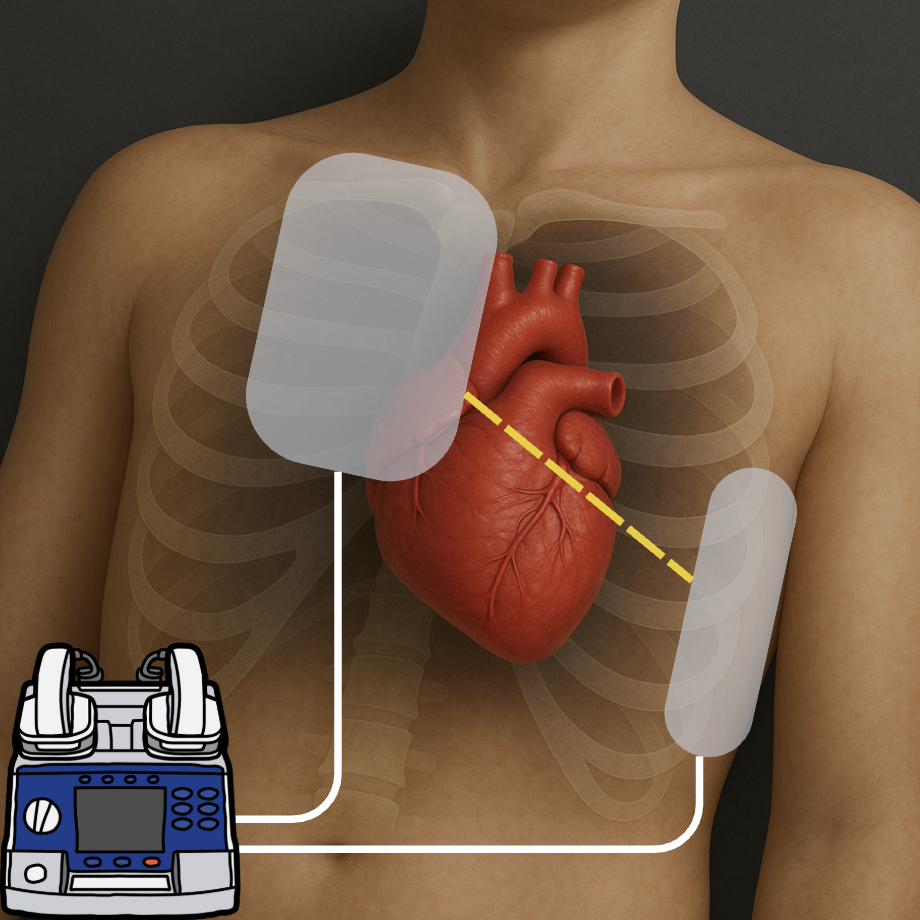

Popularised by E.R./Casualty/Holby City/Grey’s Anatomy/[insert medical TV show of choice here], an electrical cardioversion involves placing two connected pads around the chest, over the heart.

The heart is the primary electrically active organ located between the two pads, which makes it the main target of the electrical shock. During atrial fibrillation, there is disorganised electrical activity in the atria (the top chambers of the heart). These disorganised signals form self-sustaining circuits, continuously going round and round, keeping the heart out of normal rhythm.

An electrical current is delivered across the chest through these pads, simultaneously resetting (repolarising) the electrical activity in the atria. This immediately interrupts the chaotic circuits, briefly silencing all electrical activity in the heart.

This silence typically lasts for just a couple of seconds. The sinus node (the heart's natural pacemaker, located in the right atrium) recovers first and quickly resumes normal electrical activity, taking back control. As a result, the atria contract in an organised, coordinated manner once again.

After cardioversion and during normal heart rhythm, spontaneously triggered extra electrical activations can occur. If timed in a particular way, these extra beats can trigger AF again. This may occur seconds to years after the cardioversion and is challenging to predict on an individual level.

Commonly, these extra beats can originate from the pulmonary veins. Many patients take anti-arrhythmic medications designed to suppress these extra beats or can undergo a catheter ablation procedure, which blocks the electrical signals from pulmonary veins to prevent AF recurrence.

Does an electrical cardioversion hurt?

If you were awake, yes, the electrical shock would cause pain. This is because the shock stimulates nerves and muscles in the chest, causing a brief but intense contraction and pain sensation.

This is why cardioversions are always performed under heavy sedation or general anaesthetic. The actual cardioversion shock itself lasts a fraction of a second. An interesting Danish study of 276 patients found that higher-energy shocks were more likely to successfully restore normal rhythm than starting off with a low dose and working your way up. It also means less shocks per procedure and there was no significant trade-off in patient discomfort or safety. Thus, at Barts Heart Centre, we routinely start with the maximum energy dose to maximise the likelihood of success with the first shock without increasing discomfort, as patients are fully sedated.

Various studies have explored ways to improve cardioversion effectiveness, including moving the left-sided pad to the back (posterior position) or administering intravenous medications at the same time. The goal is to have the electrical current traverse through the heart and so this may be useful especially if the heart is enlarged or may be rotated due to inherited or post-operative issues.

Why can’t I keep having repeated cardioversions?

For some patients, repeated cardioversions could be reasonable, especially if a single cardioversion previously resulted in years of normal rhythm. Technically, there's no set limit to how many cardioversions you can have.

However, the procedure becomes less effective with repeated attempts, due to progressive scarring and electrical changes within the left atrium, which make it easier for those self-sustaining circuits to persist. Therefore, the time spent in normal rhythm after each cardioversion can reduce with each attempt.

Additionally, although cardioversion is generally very safe, it’s not entirely risk-free. Rare complications include anaesthetic-related complications, temporary abnormal heart rhythms, and mild skin burns where the pads were placed can happen. There are also practical considerations such as the cost and logistical challenges associated with repeatedly performing cardioversions.

Nevertheless, if you are experiencing persistent (continuous) AF, it's always worth discussing cardioversion with your healthcare team, as it is a relatively straightforward procedure that can significantly benefit many patients.